Weekend Edition: The Heartbreaking End of the Lindbergh Kidnapping

Two months after 20-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was abducted from his New Jersey home, the search for the boy ended in tragedy on the side of a road.

Welcome to the Weekend Edition of Today in True Crime. If you’re a free subscriber, you can upgrade here to receive the entire issue—which includes an extended, in-depth case profile—as well as full issues on Tuesday and Thursday. If you’re a paid subscriber, we truly appreciate your support in keeping this 100% reader-funded venture thriving.

The Heartbreaking End of the Lindbergh Kidnapping

Delivery driver Orville Wilson pulled his truck off the side of the road in a wooded area near the small New Jersey hamlet of Mount Rose on the afternoon of May 12, 1932.

When Wilson stopped, his assistant, William Allen, stepped out of the vehicle and urinated about 45 feet into the woods. There, he spotted what looked like the foot of a small child partially buried under dirt and leaves.

Police were immediately summoned to the site. The secluded spot was only four and half miles from the home of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh and his socialite wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh—the home from which the Lindberghs's 20-month-old son had been kidnapped two and a half months earlier.

The child's body was badly decomposed and bore signs that it had been ravaged by scavenging animals. Dr. Charles A. Mitchell, the county medical examiner of Mercer County, New Jersey, determined, "The cause of death is a fractured skull due to external violence."

From the state of decomposition, it was determined that the baby likely died the night of the kidnapping or shortly thereafter. Betty Gow, the baby's nurse, positively identified the remains based on two factors—the corpse had overlapping toes on his right foot, just like the Lindbergh baby, and the child's body wore a handmade shirt that Gow had sewn herself for her ward.

The discovery of the body of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was not the outcome the police, the Lindbergh family, and the anxious American public had hoped for.

Allen was understandably shaken after finding the beaten and decomposing body of the Lindbergh baby. "I just hope they get the man that did it," he said. "Nothing would be too bad to do to him."

His sentiment was echoed by people around the globe who grieved for the murdered baby, along with Charles and Anne Lindbergh. Charles Curtis, the Vice President of the United States under President Herbert Hoover, said of Charles and Anne Lindbergh, "They have my deepest sympathy, and my most heartfelt condolences go out to the bereaved mother and Colonel Lindbergh and to their families in their sorrow. It is a most shocking thing."

Betty Gow was the first to discover that little Charles Lindbergh, Jr. was missing from his crib. At around 9 p.m. on March 1, 1932, she entered the second-floor nursery in the Lindbergh home—a 390-acre rural estate on the outskirts of the New Jersey city of Hopewell—to tend the infant.

The boy was not in his crib.

Gow assumed he was with his mother, Anne, but she began to worry when she emerged from her bath without the child. Gow alerted her employer, Charles Lindbergh— a pilot who became a national celebrity after his historic trans-Atlantic flight in 1927.

The concerned father ran to the nursery to search for his son. Instead of finding his child safe in his bed, Lindbergh found an envelope on the windowsill. A handwritten ransom note, filled with misspellings and grammatical errors, demanded $50,000 for the baby's safe return.

The 1930s saw an uptick in child kidnapping for ransom cases, but the abduction of the Lindbergh baby was the most famous one of all. Driven by desperation in the face of the Great Depression's economic hardships, some ruthless individuals sought to extract money from wealthy families by stealing their most precious possessions: their children.

Newspaper and radio reports sensationalized celebrity kidnappings, and the public was fascinated by these stories. In a time when "stranger danger" hadn't yet been drilled into youngsters' heads and children were expected to obey all adults, even ones they didn't know, it wasn't too difficult to nab a child.

The Lindbergh baby, however, was stolen from his crib on the second story of his family's secluded home. After he read the ransom note, Charles grabbed his gun and ran outside to search around the house, taking the family butler, Olly Whateley, the only other male in the home at the time, with him.

On the ground, beneath the nursery window, they discovered the baby's blanket, broken pieces of a wooden ladder, and impressions in the dirt where a ladder had been placed. Lindbergh instructed Whateley to telephone the local police department in Hopewell. Lindbergh called the New Jersey State Police and Henry Breckenridge, his friend and long-time attorney.

Word of the Lindbergh baby's kidnapping caused a media frenzy. The New Jersey State Police, the organization overseeing the investigation, scoured the area for clues. Soon, another ransom note was sent. And another. In all, a dozen notes were sent either to Lindbergh or to a go-between, Dr. John Condon.

On April 2, 1932, ransom money was delivered as the most recent ransom note instructed. Included with the money were several gold certificates, a form of paper currency that was on the cusp of being discontinued.

The police hoped that the kidnapper's attempts to spend the gold certificates would draw attention to him. The gold certificates and other bills were not marked, but clever investigators copied down all the serial numbers. Lastly, the ransom money was placed in a homemade wooden box that could be easily identified later.

When the body of the Lindbergh baby was discovered roughly two and a half months after the kidnapping, the investigation shifted. Col. Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, superintendent of the New Jersey State Police and the father of General Norman Schwarzkopf—the Coalition forces commander during Operation Desert Storm—issued a statement saying:

Now that the body of the baby has been found, every possible effort will be used, and all men necessary will immediately exercise every possible effort to accomplish the arrest of the kidnappers and murderers.

"No footprints were found in the vicinity of where the baby's body was located," Schwarzkopf stated. "This whole territory was thoroughly scoured by investigators from this office, even to the extent of scraping the ground around where the body was found and putting it all in containers and bringing it to these headquarters for the purpose of test and analysis."

While they waited for the ransom money to be used, authorities focused their attention on the two most important pieces of evidence left at the crime scene—the first ransom note and the wooden ladder.

The ladder was a hastily built homemade device crafted from wood. Although it was not professionally built, the police theorized it was constructed by someone with woodworking skills.

The New Jersey State Police contacted Arthur Koehler, a wood expert with the United States Department of Agriculture's Forest Service. Koehler meticulously examined the wood to determine its age and type. He noted that the wood appeared to have been repurposed from prior use in indoor construction. His analysis would play a vital role in convicting the kidnapper.

Between August 20 and the end of September 1934, the gold certificates from the ransom drop began popping up. A total of 16 gold certificates were used at various places around Harlem and Yorkville.

Just like in old police dramas on TV, investigators—now a team comprised of members of the New Jersey State Police, the New York City Police, and special agents from the FBI—hung a large map of the New York metropolitan area on the wall of their headquarters and pushed a colored pin in it to mark the location where each of the gold certificates was used. Doing so allowed them to track the kidnapper's movement.

Next, detectives visited every bank in New York City and surrounding areas and shared the serial numbers of the ransom bills with them. Bank tellers were instructed to scrutinize every bill coming through their drawers and take note of customers at their windows. This tactic worked.

On September 18, 1934, at 1:20 p.m., a call came to investigators from the assistant manager at a bank located at the corner of 125th Street and Park Avenue in New York City.

As the manager explained, one of the tellers had just received a $10 gold certificate. The banker learned that this bill had been spent at a gas station at 127th Street and Lexington Avenue.

When the detective visited the gas station, they got their first big break in the case. The astute gas station attendant—suspicious of a man who had visited the business several times over the past week and paid for his minor purchases using $10 gold certificates—had jotted down the man's license plate number.

When the police ran the plate, it came back registered to Bruno Richard Hauptmann of the Bronx. Hauptmann was taken into custody that evening. At the time of his arrest, he had one of the gold certificates on him.

A German immigrant living in the United States for 11 years, 35-year-old Hauptmann worked as a carpenter in New York. He had served time in prison in his native Germany before illegally entering the U.S. as a stowaway.

He was married to Anna Schoeffler, a waitress, and they had an infant son, Manfried, who was born in 1933—months after the Lindbergh baby was kidnapped. For more than a decade, Hauptmann was a hard worker who never missed a day of work; however, in early March 1932, within days of the kidnapping, he suddenly began trading in stocks and quit his job.

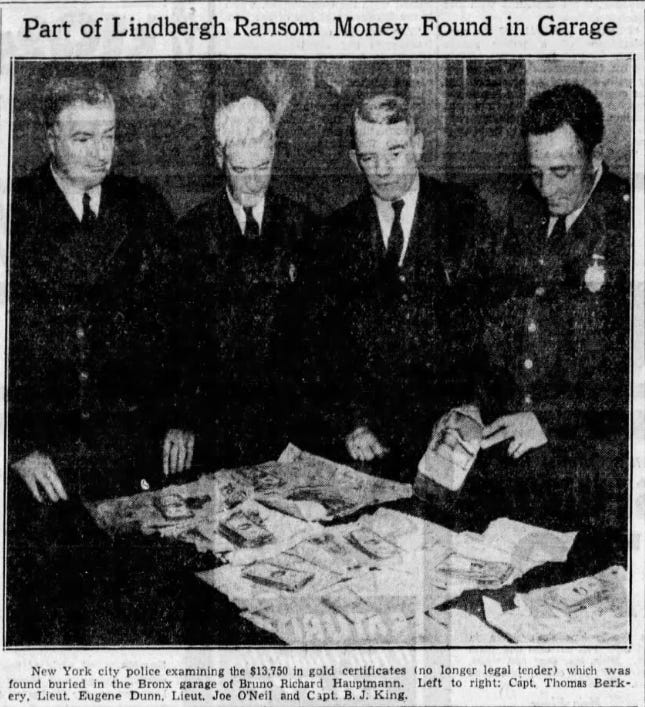

A thorough search of his home yielded some startling finds. Hidden in a gas can in his garage were gold certificates and bills from the ransom money totaling $13,000. A phone number and address belonging to John Condon, the ransom go-between guy, was written.

Police also found a section of wood in Hauptmann's attic that Koehler determined to be an exact match of the wood used to make the ladder found at the Lindberghs' home the night of the kidnapping.

Authorities obtained samples of Hauptmann's handwriting from his home and sent them to be analyzed by FBI handwriting experts. The report stated that there were remarkable similarities between his writing and the writing of the ransom notes.

Bruno Hauptmann's trial began on January 3, 1935. For the next five weeks, jurors heard the evidence—which was, in hindsight, largely circumstantial. In the court of public opinion, Hauptmann was guilty even before the trial started.

America in the 1930s was anti-immigrant and anti-German, therefore Hauptmann was vilified in the press. He staunchly maintained his innocence, claiming that a friend and fellow German immigrant left him the box of money as repayment for an old business debt. The other man died shortly afterward.

The jury wasn't buying Hauptmann's excuse. They found him guilty of first-degree murder on February 13, 1935, and he was later sentenced to death. That sentence was carried out on April 3, 1936, when Hauptmann was sent to the electric chair.

In the decades since the Lindbergh kidnapping, numerous theories have surfaced claiming that Bruno Hauptmann was wrongly convicted and executed. Other theories claim Hauptmann was guilty but that he was not the only one involved in the crime.

A recent theory even suggests that Charles Lindbergh himself—an advocate for eugenics—orchestrated the murder of his son because the child had some birth defects.

The majority of people, however, believe that the police got the right man and that Bruno Hauptmann had single-handedly committed the horrific crime of kidnapping and murdering the infant son of the most famous aviator of the 1930s.

Explore More

Read: The Case That Never Dies: The Lindbergh Kidnapping, Lloyd C. Gardner

Listen: A Shocking New Look at the Lindbergh Kidnapping & Murder w/ Lise Pearlman, Most Notorious! A True Crime History Podcast

Watch: The Circumstances Surrounding the Kidnapping of the Lindbergh Baby, Weird History

May 17, 1968: The remains of "Tent Girl" are found, won’t be identified for 30 years

On May 18, 1968, a man found a body wrapped in a thick tarp-like material in a wooded area of Georgetown, Kentucky. The woman’s body could not be identified, but it was clear she had died from a blow to the head.

Over time, the case went cold, and the woman became known as “Tent Girl.”

In 1998, a man named Todd Matthews, eager to solve the crime, helped authorities determine the identity of the woman: Barbara Ann Hackmann Taylor, who had disappeared under mysterious circumstances from Lexington, Kentucky, in 1967.

When investigators exhumed the decades-old remains, they found an exact DNA match with Barbara Ann’s sister, and the identity was finally confirmed.

Unfortunately, they weren’t able to reveal what happened to Hackmann or who killed her. The most popular theory was that her husband, George Earl Taylor, may have something to do with her disappearance.

He reportedly said Barbara had left one day, and he never saw her again, but investigators believe Taylor, a carnival worker, may have used a tarp-like material at work that was also used to hide Barbara’s remains. George passed away from cancer in 1987—11 years before “Tent Girl” was officially identified.

Explore More

Read: The Story of Tent Girl, CBS

Listen: Cold Case Solved | The 30-Year Mystery of Tent Girl, What Remains

Watch: Solving a 30-Year-Old Murder Mystery Using the Internet, VICE

May 13, 1997: Eight-year-old Kirsten Hatfield is seen for the last time

On the night of May 13, 1997, 8-year-old Kirsten Hatfield went to bed with her sister in their Midwest City, Oklahoma, home. But by the morning, she was missing, and there was little evidence to suggest who took her in the night.

Police recovered some clues as to what happened: there was blood on a windowsill of the room, and some of her garments were found behind the home. Otherwise, authorities were at a loss as to where Hatfield was, and it wouldn’t be until 2015 that advanced DNA testing led to one suspect: Anthony Joseph Palma.

The 56-year-old man was a neighbor of the Hatfields and, during the 2015 investigation, gave authorities a DNA sample that conclusively linked him to the cold case. In 2017, he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

His sentence didn’t last long, however: in 2019, Palma was strangled and killed by his cellmate, likely as a result of Palma’s crime. He never revealed the location of Hatfield’s remains, something that investigators were still hoping to uncover before Palma was unexpectedly killed.

Explore More

Read: An Oklahoma Murderer Took A Crucial Case Detail To His Grave, Investigation Discovery

Listen: MURDERED: Kirsten Hatfield, Crime Junkie

Watch: Where is Kirsten Hatfield?, True Crime Daily

Weekend Reads

35 Years Later, the Remains Known as ‘Chimney Doe’ Have a Name and a Face, The New York Times

A crack in the case: Can DNA testing give the monster a name?, USA Today

Your next true-crime fix? This sensational investigative podcast, Yahoo

Oregon Serial Killer Fears Sparked by Murders of 5 Women, Newsweek

Concerns grow for Chinese citizen journalist after supposed jail release, The Guardian

Why a New Yorker Story on a Notorious Murder Case Is Blocked in Britain, The New York Times

Arm that washed up in Waukegan, Illinois believed to belong to murdered Milwaukee woman, CBS News

Thanks for reading today’s issue of Today in True Crime! Comments, questions, suggestions, or corrections? Let us know here.